Hello readers,

Today’s piece is a step away from economics for a bit for an in-depth look at Human Society, Politics and Philosophy, including the way we conduct ourselves and a look at our civilisation in the 21st Century. We’re taking a look at this complex issue through an argumentative essay I wrote months ago on these issues.

We hope you enjoy.

“Civilisation … is a kind of disease which the various races of man have to pass through … we know of no single case in which a nation has fairly recovered from … In other words the development of human society has never … passed beyond a certain definite and apparently final stage in the process we call Civilisation…” - Edward Carpenter.

Civilisation is an imperfect means by which humanity organises itself, as a group which lives in cities. To be civilised means to take part in a civilisation, therefore accessing the characteristics of civilisation, such as an urban-rural divide or the formation of a functioning economy and political system. For one to be civilised, they live in cities and conform to its dominant values. To be uncivilised is to not engage with this form of society, and refrain from such a form of human organisation, for instance through tribalism or nomadism. Initially meaning to live in cities, the concept of civilisation became more marginalised, as the opposite of barbarism and anarchism, creating connotations of “us and them.” By the age of the enlightenment and empire-building to civilise meant to mould those viewed as inferior or unfamiliar to conform to the interpretation of what civilisation is by a dominant power in order to create a homogenous society. Civilisation is an aspirational concept viewed as superior, and civilisations strive to be “more civilised” than others.

Our civilisation is civilisation in the interpretation of today, where civilisation is classified in relation to a political borders along with its people groups, in addition to the growing forces of regionalisation and globalisation to form one “human civilisation” spearheaded by intergovernmental organisations such as the UN, EU or ASEAN. In addition, it is the ideological civilisation of liberal democracy which gave birth to the modern world.

Throughout time, many civilisations have collapsed to be replaced by new civilisations. It is often identified that the collapse of civilisation comes about as a loss of cultural identity, social complexity and the characteristics associated with civilisation. For a civilisation to collapse it must lose its cohesion, leading to its members moving towards an individualistic worldview or one within family units, as opposed to a social worldview to fellow members of the civilisation. A collapse of civilisation often results in the fall of the government and the political and economic fabric of that particular society and civilisation. There are a range of interpretations for why civilisations collapse, ranging from war, to natural disasters to famine, while it could be considered that civilisations may not collapse at all. In addition, it can also be argued that perhaps “our” civilisation is in danger from such a form of collapse, as a result of both man-made and natural threats. The evidence suggests that civilisational collapse comes as a result of threats to culture and identity, and while our civilisation as a whole is not in danger, subsets of our society are under imminent threat.

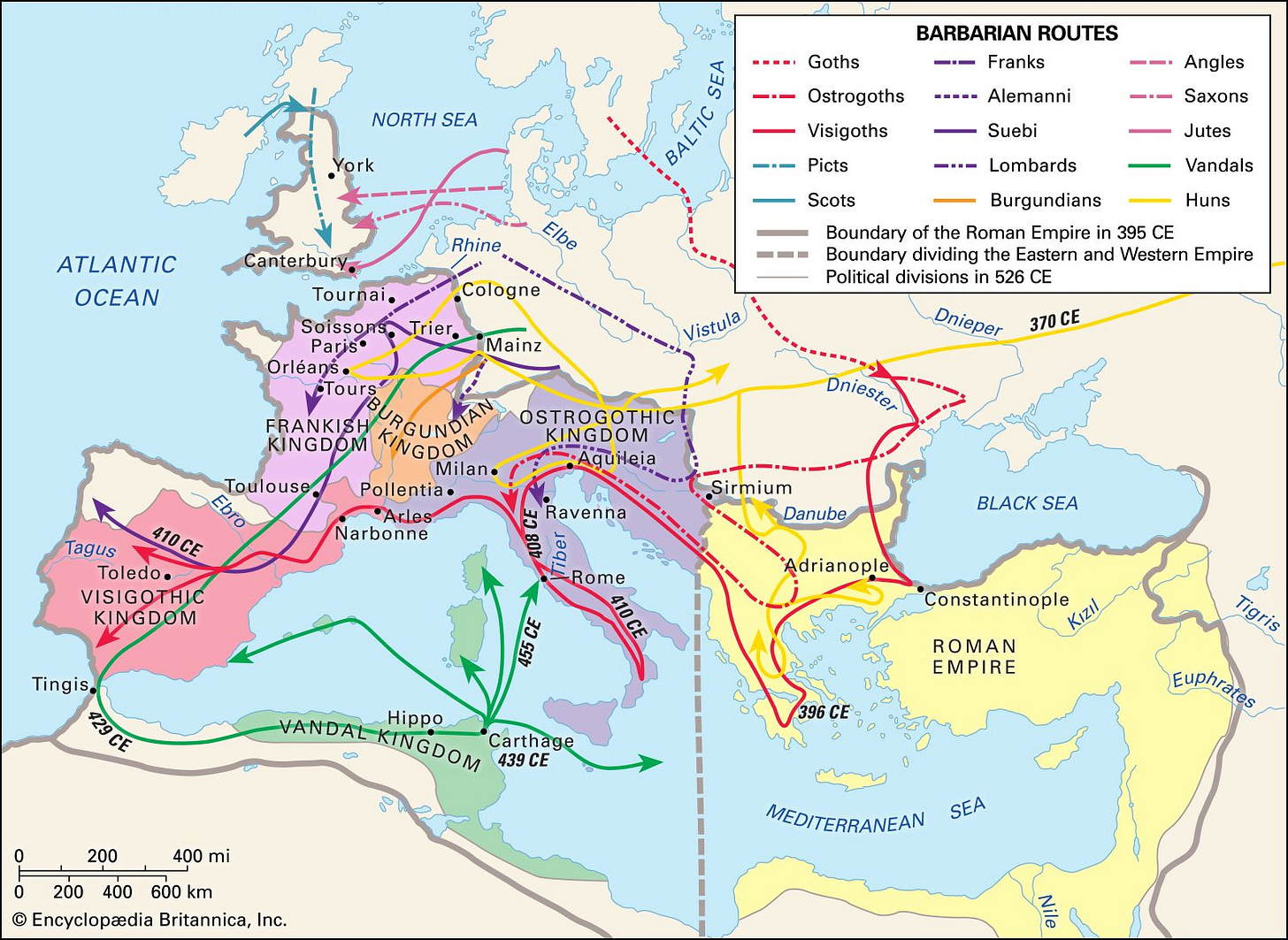

One interpretation for why civilisations collapse is due to man-made factors such as war and migration, leading to the loss of cultural identity. Take the Classical Roman civilisation, which collapsed in 476. One of the key reasons for its demise was the migration of various tribes from Eastern Europe, Germania and other areas to Roman lands. The migration period saw the meeting of incompatible civilisations. Rome, which had enjoyed a hegemony over Europe for a millennia, found that its ideas and traditions were increasingly falling to external threats, which were taking its place. This incompatibility is exhibited with the invasion of Britain by the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, which, by the time it had ended, had removed all Celtic, Brythonic and Roman aspects of British culture, replacing it with a heavily Germanised one. War and migration moved new civilisations to replace old ones to impose its new cultures within the area. Over time, the interpretation of civilisation which made one civilisation great is loss through time, and the loss of this cultural identity seals the fate of the civilisation. Civilisations are often run on the basis of a set rule of law that is agreed upon by all individuals. When that rule of law is broken externally or internally by strongmen and dictators, collapse is brought on. In this case, the Roman communal identity is challenged by “barbarians” which they viewed as inferior.

Famine and natural disasters are also viewed as another cause of collapse. When a civilisation loses its sources of food, the people within such a civilisation are unable to feed themselves, and die, leading to incohesive societies, as food resources are not shared properly and individuals begin to acquire food individually. Instead of food-producers relaying food via the economy, stealing, or self-provisioning is the main way to acquire food. Natural disasters exacerbate the famine problem. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or flooding make land uninhabitable, forcing relocation of people, or permanently ending settlement within an area. The relocation of people leads to the dispersal of culture and identity, effectively ensuring the collapse of civilisation.

Moreover, it can be interpreted that the most important cause of civilisational collapse is due to the disruption of the economic system of that particular civilisation. The economy is the backbone of most states, facilitating the transfer of goods, services and financial resources from one member of the civilisation to another. A decline in a certain set economic system due to factors ranging from uncontrollable expenses to economic stagnation contribute to causing all other factors of societal collapse, or exacerbating existing ones.

However, we must also consider that there is no collapse. Instead of a destruction of a civilisation, there is assimilation, where the ideas and interpretations of a civilisation are absorbed into that of another civilisation, whether that be through peaceful political union or through war. Assimilation does not necessarily mean a subservient civilisation becoming integrated into a dominant one (though this is often the case), but also a hybridisation of culture as a dominant conquering culture adopts the interpretation of civilisation of the conquered civilisation into its own interpretation and culture. The Roman Empire was famous for its enormous pantheon of Gods, borrowed from areas it conquered and assimilated, from the Olympians taken from Greece, to the cult of Isis taken from Egypt. Additionally, civilisations which have collapsed still influence civilisations which take its place. The legal, political and linguistic traditions of Classical civilisation still influence many other countries in the modern world despite its collapse centuries ago. By the time of Rome’s collapse, European scholars themselves viewed the age as a “Dark age” with little civilization. Only after the Renaissance or “Rebirth” of Ancient Civilisation did scholars consider the European world civilised. This suggests that the interpretations of civilisation of fallen cultures continue, even if the polity or human organisation no longer exists. Furthermore, many aspects of civilisation, such as bartering and trade continue regardless of whether a civilisation is present, and have become embedded within human nature.

Overall, it can be identified that there are a range of different reasons for why a society collapses. We have determined that societal collapse comes about namely as a result of the absence of societal cohesion between members of society. Of course, societal collapse or destruction is a fluid concept which changes over time. The evidence however, suggests that the main cause of collapse comes about as a result of economic collapse.

In regards to whether our civilization is in danger, many areas around the world suffer from many of the factors contributing to the collapse of civilisations. For example, the existence of “failed-states” such as Somalia or even the United States in the modern day is viewed as proof of this. Somalia, for instance, has a government which exists only nominally in name, with the functions of the state including tax collection, maintenance of a standing army or law enforcement severely limited. Trapped in a state of civil war, the country devolved into anarchy after the fall of the government of 1991, leaving local groups vying for control. Somali pirates, extremely publicised within the media, originally began with locals attempting to protect Somali waters from encroachment by ships dumping waste in the aftermath of the disbandment of Somalia’s navy.

Another example of failure within “our” civilisation is that of the USA, such as during the January 6th insurrection, where President Donald Trump’s followers attempted to overturn the election which would see him voted out of office, engaging in violent riots across Washington D.C.. The case study of Somalia provides a look into the failure of our civilisation in maintaining the key characteristics of civilisation, such as that of an economy or stable political system. At the same time, the January 6th insurrection provides an insight into the failures of the rule of law, the inherent part of civilisation which allows for humanity to organise itself into complex groups. The insurrection is an example of forces against order and the liberal democracy ideology which is the interpretation of civilisation in its current form, providing yet another case study into the risk of collapse.

It is also said that our civilisation is in danger due to the impact of the growing income gap within society, leaving economic parity within the world impossible. In the modern-world, there is a clear view of a “first world” that was developed in the age of industrialisation, and the “third world” consisting of those completing their industrialisation and those who are beginning to do so. In the modern day, the parity and equality between these two worlds increasingly grows apart, suggesting that with the exponential rate of growth, that parity within the modern world is impossible. Whether that means the absorption of those who failed to industrialise into a new civilisation led by those who succeeded remains unclear, though the parity gap suggests that those who are unable to keep up may collapse.

Conversely, it can also be argued that our world is not in danger. The growth of technology, communication and other influences have greatly homogenised our civilisation, powered by the impacts of globalisation. Past civilisations have been isolated ones, with a strong sense of community. However, the civilisation of today is one much larger in size, and one that is much more connected. Rapid political and economic change were identified as some of the main causes of collapse, and with globalisation, this can theoretically be tackled easily with the easy movement of people with unique skills and ideas in tackling global issues.

Finally, it is important to consider that civilisation is relative. Civilisation constantly reinvents itself and is always changing. The interpretation of civilisation in history is nothing like that of the modern world. Like Edward Carpenter theorised in his writings, civilisation is like old age and disease, one which every society must pass through and eventually “die” from. To an extent, it is healthy for collapse and rejuvenation of societies to occur. A collapse of society does not mean the destruction of technology and the socioeconomic system, but simply a reshuffling of political ideas, or shifting of consensus and the nature of human organisation which makes up civilisation. Civilisation is unavoidable, not aspirational.

To conclude, there are many interpretations as to why a civilisation may collapse, if it collapses at all. This ranges from those brought on by war and movement of people, as seen by that of the Classical Civilisations, to those as a result of famine. The evidence from the considered case studies suggests that the main cause of civilisations collapsing is loss of culture and identity. In regards to whether our civilisation is in danger, there are also many interpretations. While it can be argued that globalisation and the presence of failed-states could lead to the spreading of collapse at an unprecedented rate, the considered case studies show that our civilisation is not in danger at this point, only select few groups scattered across the world, which are threatened by the range of factors, most notably the loss of economic stability.

Bibliography

Addis, F. (2018). Rome: Eternal City. [online] Google Books. Head of Zeus. Available at: https://books.google.co.th/books/about/Rome.html?id=QGuuswEACAAJ&redir_esc=y [Accessed 29 Feb. 2024].

Bauer, P. (2020). barbarian invasions | Facts, History, & Significance. [online] Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/barbarian-invasions [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].

BBC (2018). Somalia country profile. BBC News. [online] 4 Jan. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14094503 [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

BBC (n.d.). Why societies grow more fragile and vulnerable to collapse as time passes. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240424-do-societies-civilisations-grow-old-frail-and-vulnerable-to-collapse [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

Carpenter, E. (1920). Civilisation: Its Cause and Cure - Wikisource, the free online library. [online] en.wikisource.org. Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Civilisation:_Its_Cause_and_Cure [Accessed 28 Jun. 2024].

Duignan, B. (2023). January 6 U.S. Capitol Attack. [online] Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/January-6-U-S-Capitol-attack [Accessed 28 Jun. 2024].

Ehrlich, P.R. and Ehrlich, A.H. (2013). Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1754), p.20122845. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2845.

H. Barma, N. (2019). Failed state | government. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/failed-state [Accessed 25 Jun. 2024].

History of Europe - Barbarian migrations and invasions. (2019). In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe/Barbarian-migrations-and-invasions [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

marineinsight.com (2016). Causes of Piracy in Somalia Waters. [online] Marine Insight. Available at:

https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-piracy-marine/causes-of-piracy-in-somalia-waters/ [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

Kemp, L. (2019). Are We on the Road to Civilisation collapse? [online] Bbc.com. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190218-are-we-on-the-road-to-civilisation-collapse [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

Mark, J.J. (n.d.). Civilization. [online] World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/civilization/#:~:text=Civilization%20(from%20the%20Latin%20civis [Accessed 25 Jun. 2024].

Mark, J.J. (2018). Roman Empire. [online] World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Roman_Empire/ [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].

news.un.org. (2024). Haiti: Gangs have ‘more firepower than the police’ | UN News. [online] Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/04/1148231 [Accessed 27 Jun. 2024].

Wikipedia Contributors (2019a). List of countries by Human Development Index. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_Human_Development_Index [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].

Wikipedia Contributors (2019b). New York City. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].

Wikipedia Contributors (2019c). Renaissance. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].

www.britannica.com. (n.d.). Edward Carpenter | Socialist, Poet, Activist | Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Carpenter [Accessed 14 Jan. 2025].